| ©Mitchell Diamond 2015 | Home |

Richard Dawkins’ Faith-based Theory of Religion

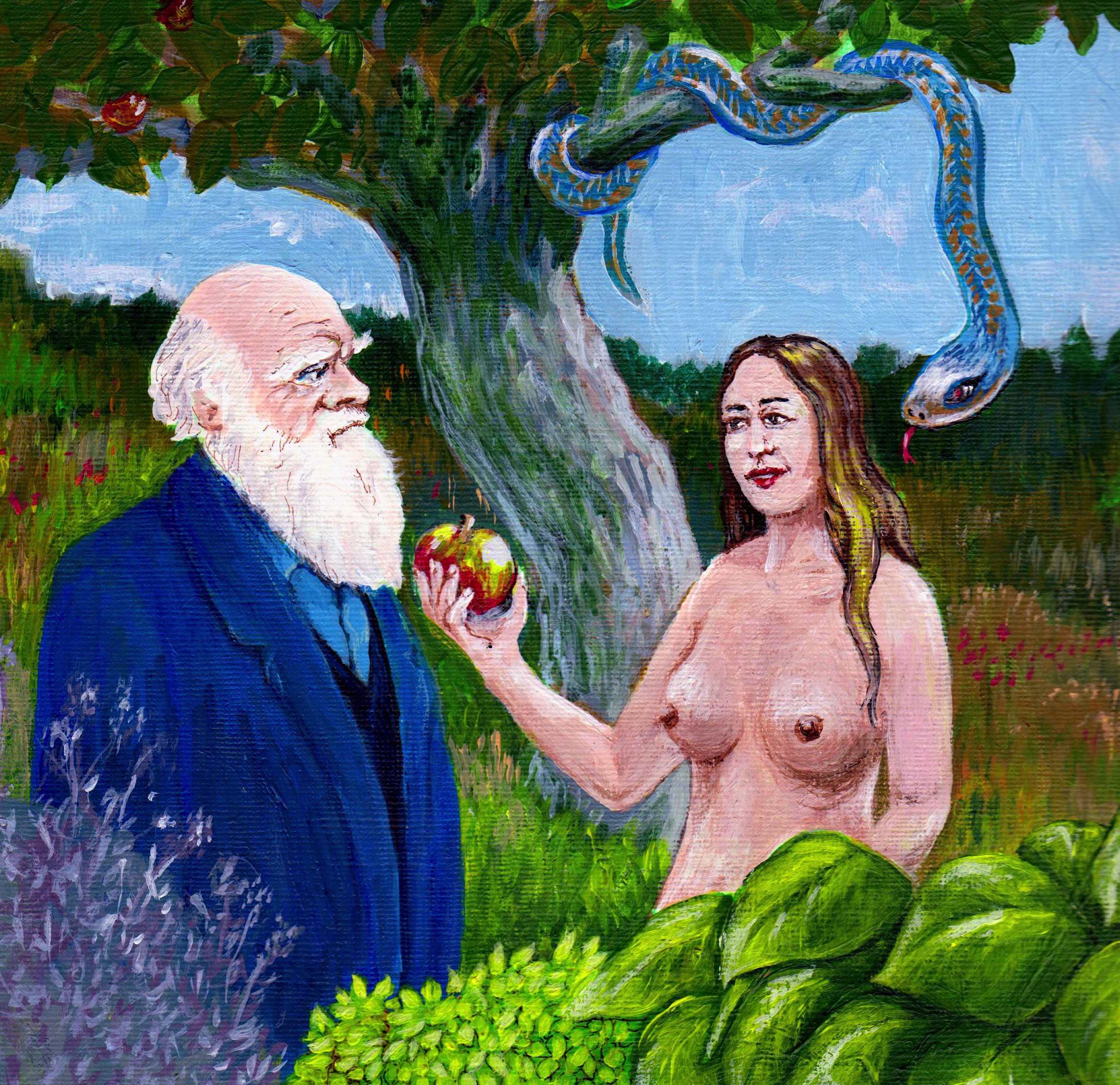

Art by Stan Engel©

Richard Dawkins is a leading evolutionary biologist and author of several important books including The Selfish Gene and The Blind Watchmaker that have significantly changed the way people understand the theory of evolution. Dawkins has become the de facto spokesman opposing organized religion and belief in God. He wrote the book The God Delusion as a screed against creationism and the illogic of religion.

Most of those who object to Dawkins’ stance do so from a position of faith. The God Delusion has generated a number of books in response with titles such as The Dawkins Delusion, Is God a Delusion?, and Deluded by Dawkins? That is not the case here. Instead, I criticize Dawkins for his own faith-based, illogical approach to the nature and origin of religion. He would have his readers believe that he maintains a consistent scientific and rational strategy in his analysis of religion, but that is not the case.

[Page numbers in parenthesis refer to the 2006 edition of The God Delusion.]

Richard Dawkins devotes several chapters in The God Delusion to the question of whether or not God exists and criticizes people’s beliefs because the existence of God cannot be proven, which, of course, is true. Here, however, it matters not one whit whether God exists or not. That is not an issue worth pursuing. The existence of God is only germane because it is an expression of human cognition, but not if God is true or real. The more important and challenging issue for Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist, and myself, is did religion evolve or is religion solely culturally acquired and passed on? For Dawkins the answer is that religion is nurture not nature, but disappointingly his assessments of religion are not based on his own evolutionary scientific logic but rather on groundless bias.

Dawkins and I agree about many things. We are like-minded in that humans or “any creative intelligence, of sufficient complexity to design anything, comes into existence only as the end product of an extended process of gradual evolution.” (52) Another point of agreement is our disdain for the farce of intelligent design. With one poignant thrust he cuts to the heart of the matter when he asks, who designed the designer?

After Dawkins makes his case for why God doesn’t exist, he moves to the more interesting and pertinent arena of the roots of religion. Sadly Dawkins deviates from his own cornerstone as he denigrates religious faith and succumbs to bouts of irrationality himself. I hate to take umbrage with Dawkins as he is mercilessly pummeled by the devout, the true believers, although I suspect he takes pride in upsetting them. Still I’m troubled when he suddenly becomes a philosopher, and his rigorous analysis of religion suffers accordingly. He jumps on the popular religion as byproduct bandwagon. A byproduct in biological parlance is a trait that did not evolve and was not selected for. Rather, it was an accidental, randomly arising characteristic that piggybacks into existence on another trait that is adaptive and selected for. Biological byproduct theory is deeply troubling and flawed. It is quite amazing that Dawkins so blithely adopts the byproduct stance. He gives the example of children being innately wired to accept and believe what their elders tell them. This has obvious benefits. Children do not put themselves in dangerous positions if they listen to parental advice. But this, according to Dawkins, has the unintended consequence—the byproduct—of making children extremely gullible, resulting in them absorbing farfetched mythologies and believing in imagined spirits.

In an April 30, 2005 interview with Salon.com, Dawkins explains:

From a biological point of view, there are lots of different theories about why we have this extraordinary predisposition to believe in supernatural things. One suggestion is that the child mind is, for very good Darwinian reasons, susceptible to infection the same way a computer is. In order to be useful, a computer has to be programmable, to obey whatever it’s told to do. That automatically makes it vulnerable to computer viruses, which are programs that say, “Spread me, copy me, pass me on. Once a viral program gets started, there is nothing to stop it.”

Similarly, the child brain is preprogrammed by natural selection to obey and believe what parents and other adults tell it. In general, it’s a good thing that child brains should be susceptible to being taught what to do and what to believe by adults. But this necessarily carries the down side that bad ideas, useless ideas, waste of time ideas like rain dances and other religious customs, will also be passed down the generations. The child brain is very susceptible to this kind of infection. And it also spreads sideways by cross infection when a charismatic preacher goes around infecting new minds that were previously uninfected. (http://www.salon.com/2005/04/30/dawkins/; accessed 2013July13)

While Dawkins is a bit hyperbolic about children obeying their parents and being gullible, young children are certainly sponges who are predisposed to absorb and retain the mores and traditions of their family and culture, which, in general, helps the child mature and become a successful individual in society. A larger problem for Dawkins is his assumption that religious practices and beliefs are not evolutionarily adaptive, which suggests to him that they are byproducts. Plenty of evidence, however, indicates just the opposite although the debate rages. More importantly to this essay, though, is how Dawkins ignores his own axiom: who designed the designer? How did the first parents and clergymen acquire these beliefs that they then pass on? Where does this religious infection start and why? He implies that in some cases it started with a charismatic preacher who was motivated to take advantage of the mentally infirm, but religion started in tribal bands tens of thousands of years ago and was practiced by all the tribepeople often with the help of the shaman. That’s where the origin of religion happened and where Dawkins should be investigating, but for him, those aren’t questions worth pursuing.

I completely agree with Dawkins when he says, “Darwinian selection habitually targets and eliminates waste. Nature is a miserly accountant, grudging the pennies, watching the clock, punishing the smallest extravagance.” (190) Any organism that squanders its efforts on activities that don’t contribute to its survival and reproductive success will not be favored in the competition of natural selection. Organisms that don’t waste resources have better odds of survival and passing on their genes for efficient behavior. By extension anything that is ubiquitous in a population or species is adaptive and is selected for.

Continuing with his religion as byproduct idea, Dawkins describes how the brain is organized into modules for dealing with specialized needs and that “religion can be seen as a byproduct of the misfiring of several of these modules, for example the modules for forming theories of other minds, for forming coalitions, and for discriminating in favour of in-group members and against strangers.” These brain modules are “vulnerable to misfiring in the same kind of way as I suggest for childhood gullibility.” (209) According to Dawkins, the misfiring of brain modules leads to the wide variety of religious behaviors that are enormously expensive in evolutionary terms, yet religion isn’t selected against. It continues to exist in all societies apparently as a kind of benign brain error except, as Dawkins is fond of pointing out, it isn’t all that benign. In only 19 short pages Dawkins conveniently forgets how natural selection punishes the smallest extravagance. Something that is without any adaptive or advantageous purpose should have been eliminated by evolution, the miserly accountant. In addition, if misfiring brain modules are functional errors, it makes an even stronger case why religion should not have developed and persisted and why Dawkins’ own brain modules are misfiring. Evolution, to which Dawkins claims obeisance, is suddenly relegated to the back of the bus. He makes the argument fit his agenda rather than the science.

Dawkins is circumspect about the religion as byproduct theory as “the details are various, complicated and disputable.” (218) This is the best he has to offer? His acolytes aren’t going to be put off by his disclaimer. Why doesn’t he stick with evolution for which the details are indisputable? He ultimately has no good doctrine for the origins of religion, only that he doesn’t like religion so he has to pitch whatever he can lay his hands on. In Dawkins’ defense, there has been no adequate explanation for why many people cling so passionately to religion. Based on the current models, it’s understandable that he doesn’t see a logical reason for people to believe in God or religion. (See brief description of a theory of religion that doesn’t depend on byproduct or other quasi-theories.) But then he also makes the inappropriate assumption that people are logical. He obviously takes pride in his own scientific acumen and presumes that, even if others aren’t as rational as he, they should be, although he might want to reconsider his own position on rationality.

For the torchbearer of modern evolutionary theory to expound evolution except when ideology interferes is tragic. When the going gets tough he abandons logic as assiduously as his creationist adversaries. It’s disingenuous and disappointing. Dawkins makes the inappropriate leap that because there are, in fact, no God or gods, devils, angels, cherubs, or what have you out there, then there’s no good reason to believe in them. He denies or ignores any psychological or innate need to believe in greater powers. The existence of God is a very different issue from the innate need for religion, but sadly Dawkins needs his faith-based anti-religion agenda as dearly as a clergyman must believe in his God-based faith. To propose that religion is an exception to the theory of evolution is to imply that evolution is not an adequate explanatory device and that evolution should therefore not be the unifying theory for the origin and development of life forms. This is akin to siding with creationists and cannot stand.

| ©Mitchell Diamond 2015 | Home |