| ©Mitchell Diamond 2011 | Home | Book ToC | Summary |

Introduction to The Split Theory of Religion

In this introduction, I propose a new theory for the origin and purpose of religion. For those who are heavily invested in existing theories of religion, this theory may seem foreign and unlikely as it challenges long-held assumptions. But for those who aren't blighted with insurmountable prejudice, does this theory rely on sound evolutionary and psychological science? Does it maintain internal consistency? Does it present an explanation that addresses observed religious behaviors? That is obviously the test of validity and one I hope to achieve.

The proposed origins and functions of religion vary widely. Anthropologist Stewart Guthrie said, “Anthropology and other humanistic studies lack an adequate theory of religion. [They] have found no single paradigm. No theory or even definition of religion is generally accepted.” (Guthrie 1980 p. 181) Thirty years after Guthrie wrote this, little has changed. There is no consensus whether religion evolved by natural selection and is in our genes or is strictly a cultural phenomenon. Does religion serve a necessary purpose or is it an accidental by-product of habits of mind, the mental residue left over from other behaviors that are important for human survival? The theories for the purpose of religion remain as elusive as ever. Considering the importance religion has for most people, it's quite perplexing that the explanations remain wanting.

Theories of religion include anthropomorphizing the world; attempting to explain and control the world; not explaining the world by contradicting experience; constructing an ultimately reasonable universe; forms and acts which relate man to the ultimate condition of his existence; or wish-fulfillment to name a few. (Guthrie 1980 p. 182-183) The theories that have received the most widespread attention recently are to assuage the fear of death, to answer the existential mysteries, to provide group cohesion, and the Agency Detection Device. Obviously, it's necessary to explore the details for evaluation, but even that doesn't help. They all describe aspects of religious behavior or belief and have legitimacy. All have serious shortcomings and none are adequate to account for all religious phenomena. None adequately account for how religion is adaptive and improves evolutionary fitness.

It seems as if any theory can be made to seem reasonable and describe some phenomenon, and it's certainly the case with religion. Like many aspects of the social sciences, the foundational assumptions for religion are insufficient. Anthropologist Scott Atran said, “You can find functional explanations [for religion] and their contraries, and they're all true.” (Glausiusz 2003) It's like swimming in mud. There's a lot of arm waving but not a lot of movement.

What's needed is to take a step back and consider a theory that looks beyond the above-mentioned proposals and wraps a theoretical umbrella around all intrinsic religion, the personal feeling of the spiritual. I propose The Split theory of religion. Succinctly, intrinsic religion is a compensating mechanism for higher-order consciousness. Early in human evolution, developing human cognition divided into two paths: higher-order consciousness took one path, and religious feeling took a different and parallel path, but they were essentially two projections from the same source.

The support for The Split theory requires three legs of a stool to stand. The first leg is consciousness, or more exactly what consciousness is not. While our understanding of consciousness is still sketchy, much brain biology of the last several decades has shown that consciousness—self-awareness and volition—is not the controlling executive that many believe it to be. By far most of our behavior is driven by unconscious automatic systems.

The second leg is the role of emotion. In their paper The Neural Substrates of Religious Experience, UCLA physicians Jeffrey Saver and John Rabin propose a unifying hypothesis: emotions are the one constant of all religious experience. (1997) They aren't the first to understand that emotions are the unifying thread and physiological manifestation of religion. People have long recognized the role of emotions in religious behavior. Indeed, a quick review of theory of religion books and articles reveals that emotion underlies all the theories. Recent studies suggests that ritual behavior—making or listening to music, for example—stimulates the brain's reward centers deep in the limbic system, the seat of emotions. (Blood and Zatorre, 2001) Emotions are evolved systems that ensure our survival. Religion puts us in touch with our emotions by suppressing consciousness therefore religion is adaptive. This is to say religion evolved biologically, and the propensity for religion is inherited and in our genes.

The third leg of the stool is the five ritual behaviors: music, dance, art, mythology, and prayer. Rituals are the behaviors of religion and have several aspects in common: they are seemingly non-utilitarian; they are first observed historically in ancient tribal religions; they are ubiquitous in all cultures; and they all elicit emotions. Religious rituals are behavioral adaptations that inhibit consciousness and prompt emotions.

The first part of The Split theory focuses on the problem of consciousness as it is a most difficult and critical aspect to my argument. The scientific evidence is plentiful and compelling and is taken up in successive chapters here, but of course, it won't convince those who believe with a religious-like ferver that consciousness has only a beneficial contribution to Homo sapiens. The studies of many neuroscientists and psychology professors are cited to substantiate all claims, but in this introductory chapter, The Split theory of religion is fleshed out with allegory, metaphor and only a little science.

Does a frog have consciousness? Does it have self-awareness or can it access a vast array of short-and long-term memories for complex cognitive evaluation? Does it have any of the characteristics we associate with higher-order consciousness such as the ability to use symbols or imagine what someone else is thinking? No, a frog doesn't have that kind of consciousness. So what is it like to be a frog, to be without self-awareness? It's hard to imagine. Since we all have consciousness, how do we envision the absence of it? It's like asking someone not to think about holding a pen. Consider that the lack of consciousness is like your consciousness before you were born, even before you were conceived. Remember that? Unless you can recall previous lives, you don't remember anything; it's a big, black blank. It's not void, as that implies an empty space. It simply doesn't exist at all. In the computer programming world, it's called NULL, meaning the absence of anything. That's what the consciousness of a frog is like. The frog is completely capable of surviving and reproducing, driven by its genetics and its telencephalon forebrain that gives it its learning potential. The frog brain is wired to be capable of a limited amount of learning, but consciousness doesn't enter into how a frog learns. When the frog's ecosystem changes beyond a certain range, the frog is toast. Its ability to migrate to better climes is limited. It can't dig for underground water in a drought. It can't modify its environment within its own lifetime. For most of the animal kingdom, this lack of consciousness is the standard. Although some birds and mammals might have glimmers of consciousness, the vast majority of animal species are NULL for higher-order or awareness consciousness.

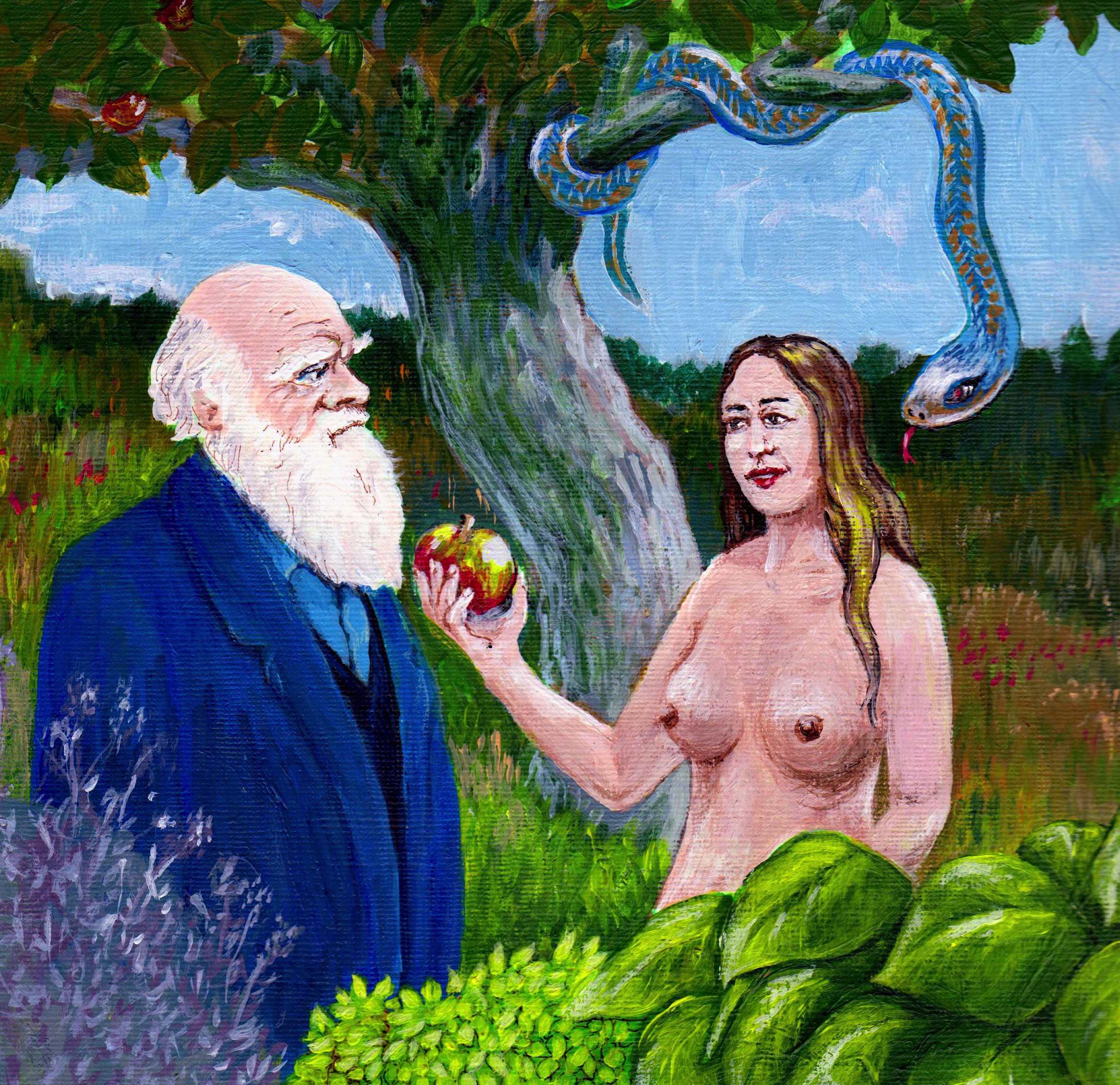

Fall From Grace

First God made heaven and earth the Bible starts out. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep. In only a page or two, God created the rest of the world, including animals and humans. He put the first people in Eden, the paradise where everything was in perfect harmony. Adam and Eve, who were naked, were not ashamed because they had no knowledge of shame. Theirs was a state of innocence because they were without knowledge or consciousness. The serpent told Eve that eating the apple would open her eyes, and she would be like God knowing good and evil.

The Garden of Eden was described as a place of purity where there was no judgment, no right or wrong. Just as some people rationalize the six days of creation as a metaphor for the evolution of the cosmos including life on earth, the Garden represents a metaphorical closed-eyes non-conscious unity, a oneness representing the state of animal existence without consciousness. Think of the Garden as symbolizing the state of instinct or frog preconsciousness. Eating the apple of the tree of knowledge and getting cast out of the Garden is the evolutionary transition from the preconscious to dichotomous consciousness in which there exists the tension of opposites—in and out, good and evil. Essentially the rest of Bible, and religion in general, is an attempt to reconcile the opposites. It may be thought of as the desire to return to the blissful state of unawareness or non-consciousness, or at least to ameliorate the strain created by consciousness to solve the problems of survival that originally belonged exclusively to instinct.

Carl Jung was keenly aware of this psychic conflict. In Modern Man in Search of a Soul, he sums up the human condition:

“It is the growth of consciousness which we must thank for the existence of problems; they are the dubious gift of civilization. It is just man's turning away from instinct—his opposing himself to instinct—that creates consciousness…As long as we are still submerged in nature we are unconscious, and we live in the security of instinct that knows no problems. Everything in us that still belongs to nature shrinks away from a problem; for its name is doubt, and wherever doubt holds sway, there is uncertainty and the possibility of divergent ways. And where several ways seem possible, there we have turned away from the certain guidance of instinct and handed over to fear. For consciousness is now called upon to do that which nature has always done for her children—namely, to give a certain, unquestionable and unequivocal decision. And here we are beset by an all-too-human fear that consciousness—our Promethean conquest—may in the end not be able to serve us in the place of nature.” (1933 p. 110)

The original sin was the human acquisition of consciousness, which separated us from frog non-conscious unity and gave us the capabilities of God-like knowledge. Consciousness also gave humans the angst of contradictions inherent in the awareness of opposites. Before consciousness, animals lived without the ability to hold complex concepts and thoughts. They did not have the capacity to consider more than one or two conflicting scenarios; any decisions that had to be made were essentially automatic choices. For an animal there is no good and bad. There is only the singular constant of non-conscious existence without judgment.

Professor of Religious History Mircea Eliade took a similar approach towards the religious connection to human origins. Eliade understood that religion developed at the beginning of human time, or as he referred to it, in illo tempore, literally “at that time,” meaning the specific event, but indeterminate time in the past, when people fell from grace. He also used the less than politically correct term of “savages” for pre-literate peoples but understood that they, too, shared the same mental experiences as us moderns.

“The savages, for their own part, were also aware of having lost a primitive paradise. In the modern jargon, we may say that the savages regarded themselves, neither more nor less than if they had been Western Christians, as beings in a ‘fallen' condition, by contrast with a fabulously happy situation in the past. Their actual condition was not their original one: it had been brought about by a catastrophe that had occurred in illo tempore. Before that disaster, man had enjoyed a life which was not dissimilar from that of Adam before he sinned.” (1975 p. 43)

Present time, which Eliade called profane time, was of little consequence compared to what he called sacred time when humanity was born. It was the religious act through ritual that was the universal requirement all humans must perform to symbolically return to the beginning time. People absolutely have the instinct to return to the sacred time, which of course they can't do in reality, so they continually visit through religious practices. Eliade said,

“Among all these paleo-agricultural peoples, the essential duty is the periodic invocation of the primordial event which inaugurated the present condition of humanity. All their religious life is a commemoration, a re-memorising. The Remembrance, reenacted ritually—therefore, by the repetition of the primordial assassination—plays the decisive part: one must take the greatest care not to forget what happened in illo tempore.” (1975 p. 45)

People cannot disdain their past, as the need to remember is part of our genetic heritage. What the religious ritual attempts to do is metaphorically recall the original condition of humanity, to connect us to a time incipient to consciousness where the innocence of perfect oneness resides in frog blank blackness, and instinct is the arbiter of behavior.

From this interpretation of the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, one might get the notion that consciousness is a bad thing. Optimistically, the best I can say is that consciousness is a mixed bag. It enables people to accommodate novel situations and suggest a course of action through the ability to hold and compare a vast array of input from senses and memory. It supports planning and rehearsal—the action of learning—in preparation for handing off practiced behavior to automatic procedures. Consciousness is also theorized to have retrospective veto power, so it can intervene after the fact. Whereas animals rely primarily on innate reflexes for survival, we humans now have options and choices. However, everything good about our species that we believe derives from consciousness—our superior memory and thinking, our taming of the land, our rich culture and technology—comes at a cost. We are afraid of dying, we question our purpose in life, we agonize over our decisions. We have gnawing existential anxiety because we have consciousness. In a world without consciousness, ignorance is bliss.

Even though the scientific knowledge of how consciousness works remains fragmentary, brain researchers are discovering that what we do know about consciousness is not what most of us think it is. People have the sense that they are in control of their lives and moment to moment decide intentionally what to do next. It isn't quite so straightforward. Our perception and feeling of consciousness is very different from the actual conscious processes themselves, and is, in fact, to a degree illusory. Because it smacks directly into people's most fervent beliefs and desires about themselves, it's very difficult for many to accept. The evidence that our conscious volition is not what motivates us is actually quite overwhelming and comes from several areas of study. People who suffer localized brain damage lose specific functionality, which often reveals how neural operations work independently of rational or thinking tasks. Also, direct research on brain structures reveals how pathways carry information that doesn't reach awareness consciousness yet still has impact on the subject. Cognitive psychologists are able to design experiments that isolate factors influencing behavior. What they find is that it's quite easy to manipulate people unconsciously through various subtle and not so subtle cues. It happens every day, for instance, when someone's emotions effect another's emotions.

Our behavior is not subject to real-time conscious introspection or control. Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran says on the first page of A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness, “Your conscious life, in short, is nothing but an elaborate post-hoc rationalization of things you do for other reasons.” (2004 p. 1) By far most human behavior is like the behavior of other animals, driven by unconscious emotions, out of sight and out of our conscious mind. Most of consciousness is like the TV sports announcer describing the play you've already seen. It's nice to have the analysis of what's already taken place, but it doesn't change what happened.

Even in-the-moment consciousness is trailing behind, watching the activity of the emotional unconscious and pestering, “Don't forget me; listen, I have something to say here.” We are aware of the sustained chatter, the internal discussion that goes on in our heads. That's consciousness doing its job, checking in, monitoring events, always observing and commenting. Consciousness evolved to constantly query and offer assistance, but the brain chatter can be annoying and, in some cases, even misguided. Researchers have shown that when feelings conflict with conscious goals or desires, people rationalize by creating scenarios to fit the emotion. (Schiffer 2000 p. 88, Ornstein 1997 p. 77) When college students were asked to analyze their feelings about a dating relationship, they changed their attitude towards their dating partners over time far more than those who didn't analyze their dating relationship, and it wasn't because the introspection made them more accurate. On the contrary, Timothy Wilson wrote in Strangers to Ourselves, “People brought to mind reasons that conformed to their cultural and personal theories about why people love others and that happened to be on their minds...there is a certain arbitrariness to these reasons...people construct a new story about their feelings based on reasons that happen to come to mind.” (2002 p. 169) People draw from cognitive or emotional predispositions or external influences to justify their state of being, which may or may not reflect the reality of the moment.

In Philosophy in the Flesh, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson begin with the premise that our mental processes are almost wholly unconscious. After listing several unconscious behaviors necessary to hold a conversation, they say, “Cognitive scientists have shown experimentally that to understand even the simplest utterance, we must perform these and other incredibly complex forms of thought automatically and without effort below the level of consciousness. It is not merely that we occasionally do not notice theses processes; rather, they are inaccessible to conscious awareness and control.” (1999 p. 11) Instead of the common belief that the unconscious exists in relation to consciousness, it is innate unconscious neural processes that are incipient, and consciousness is a Johnny-come-lately, both evolutionarily as well as contemporaneously.

Evolutionary changes to the human brain dictate that instinctual behavior relinquish some control of the organism to learning—functions that are flexible and can modify behavior in an individual's lifetime. However, this capacity that humans excel in did not evolve to replace existing cognition, only to complement it. The seemingly limitless choices humans are capable of, if not curbed, are sources of grief. The anthropologist Roy Rappaport said,

“The very intelligence that makes it possible for men to learn and behave according to any set of conventions makes them understand that the particular set of conventions by which they do live, and which often inconveniences them or even subjects them to hardship, is arbitrary. Since this is the case, they may be aware that there are, at least logically, alternatives. But no society, if it is to avoid chaos, can allow all alternatives to be practiced. For each context or situation, all but one or a few must be proscribed and the proscriptions must somehow be made effective. Thus human societies are faced with containing what Bergson called the ‘dissolving power' of their intelligence.” (1971 p. 32)

Endless choice is not a good thing. People find it very difficult to function if they have to make conscious decisions about every aspect of their lives and can easily get overwhelmed. Humans simply aren't designed to have to frequently weigh options. No animal is. A little bit of consciousness is a nice-to-have, but too much is a burden. You don't want to consider your options when the bear is coming after you. That's when the evolutionarily ancient fight or flight response, an emotional reaction, kicks in and overrides any conscious ruminations. The Homo sapien who thought about his predicament too long didn't leave offspring.

There is an ongoing tension between our innate drives and the persistence of our consciousness. While we have freedom to consider alternatives, we also have to shoulder the burden that consciousness has no absolute answers to offer. At least some of the anxiety and alienation of modern times is the result of having too much choice and no essential knowledge with which to make decisions. There is no fundamental truth or reality accessible solely to consciousness, no pure objectivity or rationality. Consciousness can accumulate a lot of memory details for evaluation, but it remains the purview of unconscious emotions to make the decisions.

The Split

Now it's a funny thing about Darwinian evolution. We tend to think of it as a one-way street in which organisms progress and improve as natural selection whittles away the less fit. Rather, evolution should be thought of as a series of compromises. Competition for survival and reproductive success are never-ending struggles, and evolution continually rolls the dice, experimenting with different combinations of genes (genotypes) and characteristics (phenotypes). Whoever survives and reproduces has won the short-term evolutionary battle. In no way, however, should that suggest that any one of those winning organisms is ideally adapted to their environment. They just happen to be good enough at the moment to pass their genes to the next generation.

A classic example is the compromise between upright walking and childbirth. Anthropologists Wenda Trevathan and Karen Rosenberg state, “The complex twists and turns that human babies make as they travel through the birth canal have troubled humans and their ancestors for at least 100,000 years.” (2003 p. 82) This is because bipedalism required significant changes to the pelvis. Instead of being designed to support just the rear portion of the body like in chimps, the pelvis now supports the entire weight of the head and torso. On top of that, the selection pressure for a great oversized brain pushes the cranium to grow larger in utero. This makes childbirth riskier in humans than in other mammals. This evolutionary compromise is like Newton's third law of motion—for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. The evolutionary pressures to select upright gait and brain size come at the expense of facile childbirth. “It's the price we pay for our large brains and intelligence.” (2003 p. 82) To endanger both the fetus and mother through the increased risk of childbirth for the benefits of a larger brain and upright locomotion means that bipedalism and large brains are extremely important to human evolutionary success.

The fallen condition of humanity is the strain between our newly acquired consciousness and the non-conscious emotional systems that served our ancestors for hundreds of millions of years. The mental Split is the co-evolution of consciousness on the one hand and the simultaneous evolution of a compensating mechanism to offset the downside of consciousness on the other. That compensating mechanism is intrinsic religion. It's the equal and opposite reaction of Newton's Third Law. Humankind's mental evolution was a schism in brain capability very much like the inherent conflict between childbirth, our large brain, and upright walking. Religion evolved because those who, through their religious behaviors, reined in consciousness and maintained reliance on their emotional instincts—or at least kept a balance between the two—survived and reproduced preferentially.

The word religion derives from the Latin religio, which some interpret to mean that which attaches, retains, or binds, perhaps a moral bond. For many atheists and agnostics, the bondage concept is apt as they find organized religion burdensome and manipulative. But Jung interpreted the etymology of religion in a different way. “This original form of religio (‘linking back') is the essence, the working basis of all religious life even today, and always will be.” (1990 p. 160) Linking back is revisiting instinctual emotions. Consciousness must be restrained and brought face-to-face with our primordial nature. Inner religious behavior is an attempt to honor one's innate emotional spirit.

Our animal nature remains foremost despite our obscenely big craniums, and this explains why religion is a biological, evolved adaptation. Our biology makes us who we are, and anything that dissuades or confounds our innate guidance is a potential threat to our well-being and survival. Consciousness has immense value, but it also has the tendency to interfere with our instinctual nature and throw us off track. It can only secondarily provide the guidance for continued evolutionary success. Our emotional genetic inheritance is the first line of defense.

Splitori

The expression of religious fervor takes many forms, but in general, there are conspicuous consistencies in the way in which people practice intense spiritual passion. Whether from the faiths of the East like Hinduism and Buddhism, the self-help books filling libraries and bookstores, or the Jewish Kabbalists, the Muslim Sufis, or the Christian mystics, the language of deep religion is strikingly similar. In all traditions, the spiritual journey describes a process for reaching a sacred union, oneness, the absolute, the infinite, nirvana. One achieves this state by extinguishing ego consciousness—losing the self, one's boundaries, or material craving. The passage to the spirit world means letting go of the tangible world. The mystical mind achieves a state of perfect understanding, clarity, and rapture devoid of the perception of time and space. Reaching the sacred bestows a sense of immortality and connection. These descriptions of the spiritual are practices that quiet consciousness and mollify the tension of opposites. The ultimate mystical union of Eastern religious thought is the elimination of suffering through the dissolution of dichotomies. Remove conscious awareness to reveal the original unity of the blank, NULL frog mind. All religious traditions have exercises that result in the mitigation of consciousness.

Wayne Teasdale, both a practicing Catholic and a Hindu monk, said, “For thousands of years before the dawn of the world religions as social organisms working their way through history, the mystical life thrived. This mystical tradition, which underpins all genuine faith, is the living source of religion itself. It is the attempt to possess the inner reality of the spiritual life, with its mystical, or direct, access to the divine.” (2001 p. 10-11) People in all cultures witness or experience this sense of religious rapture to varying degrees.

These descriptions of the religious experience say the same thing—by silencing consciousness, self-awareness, and the knowledge of opposites, one can achieve the sense of the sacred, the state before human time when we lived in frog NULL blankness and unconscious instincts ruled. Without consciousness there is no I, no thou, no top or bottom, no life or death. Without consciousness there is only the all-encompassing oneness that is without form. Andrew Newberg, a neuroscientist who scans and studies the brains of people praying or meditating and author of several books about religion and belief, says, “No matter what specific methods any given tradition of mysticism might employ, the purpose of these methods is almost always the same: to silence the conscious mind and free the mind's awareness from the limiting grip of the ego.” (2001 p. 117)

This perfect union, this infinitely spiritual, is not available to our mortal comprehension, for to think is to wallow in the light of consciousness, which means judging through the filter of polarities. Consciousness delivers us to the profane and obscures the sacred. Zen Buddhists say the barrier to satori (enlightenment) is the conscious or rational mind. In Zen religious philosophy, one cannot train to achieve satori because that requires conscious effort. Rather, Zen masters use riddles called koans that are supposed to show the fruitlessness of such mental effort. In one example, the new monk is asked to discard everything. “But I have nothing,” the monk replies. “Discard that, too!” demands his master. Another koan says if sitting in meditation leads to enlightenment, then frogs must be enlightened—the NULL blankness of all mystical achievement.

Religion is the mechanism for returning to the original unity of mind before The Split, but after a few million years of homonid brain evolution, we humans are far beyond the actual return to the unity of pre-consciousness. The best we can do is frequently visit through religious ritual. While homage to in illo tempore, the beginning of human time, is still the goal for the mystic seeker, the reality for the typical religious person is more about integrating The Split rather than the journey to achieve the Absolute. We live in the rational world and embrace our consciousness. At the same time we are attracted to and enjoy the ritual behaviors that suppress consciousness and evoke emotions. The specific religious traditions we learn are no different than the specific language we acquire. The desire and ability to acquire both language and religion are genetically driven. We engage in religious rituals because we are hard-wired to do them, and we get emotional pleasure or satisfaction from them.

The interplay between consciousness, religious ritual, and emotion is a constant negotiation. The feelings engendered by religious acts and observances range from negligible to overwhelming, as when someone attains the elation of the unified state. How do emotions change as a result of religious behavior? Does ritual behavior—the actions of religion—spark specific emotional content or does the ritual have a generic effect on suppressing consciousness, which opens emotions to whatever the organism's needs are at the moment? The interaction of the human emotional system and religious behavior is an arena ripe for examination.

There are many challenges to explaining how and why religion biologically evolved. Why did people create supernatural agents (gods), the mostly human-like entities that people invoke to populate their elaborate religious doctrines? If religion has a biological basis, does the imagining of gods as well? Do religious behaviors improve people's well being, and if so, how? The Split theory provides a framework with which to approach and answer these questions. The theory offers a method for understanding the origin of religion, this most befuddling aspect of human nature, and can be used as the basis to further investigate the evolutionary origins of religion.

Blood, Anne J. and Zatorre, Robert J. "Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion" PNAS. V. 9 No. 20:11818–11823. 2001

Eliade, Mircea. "Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries." New York: Harper Colophon Books. 1975

Glausiusz, Josie. "Discover Dialogue: Anthropologist Scott Atran." Discover Magazine, Oct. 2003 http://discovermagazine.com/2003/oct/featdialogue. Accessed 7Feb2011.

Guthrie, Stewart, et al. 1980. "A Cognitive Theory of Religion." in Current Anthropology, V. 21, No. 2. (Apr., 1980),181-203.

Jung, Carl. "The archetypes and the collective unconscious" New York: Princeton/Bollingen. 1990

Jung, Carl. "Modern Man in Search of a Soul." New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. 1933

Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark. "Philosophy in the Flesh" Basic Books. 1999

Newberg, Andrew, D'Aquili, Eugene, and Rause, Vince. "Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief" New York: Ballentine Books. 2001

Ornstein, Robert. "The Right Mind, Making Sense of the Hemispheres." Harcourt, Brace & Company. 1997 downed

Rappaport, Roy A. "The Sacred in Human Evolution" Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. V. 2:23-44 1971

Rosenberg, Karen R. and Trevathan, Wenda R. "The Evolution of Human Birth" Scientific American. May 2003, 80-85

Saver, J. and Rabin, J. 1997. "The Neural Substrates of Religious Experience." Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. V. 9 No. 3, 498-509

Schiffer, Fredric. "Can the Different Cerebral Hemispheres Have Distinct Personalities? Evidence and Its Implications for Theory and Treatment of PTSD and Other Disorders" Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. V. 1(2), 83-104.

Teasdale, Wayne. "The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World's Religions" Novato: New World Library. 2001

Wilson, Timothy D. "Strangers to Ourselves" Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2002

| ©Mitchell Diamond 2011 | Home | Book ToC | Summary |